The Job Market Has Not Always Been Bad

I would like to drive a stake through the heart of the myth that the academic job market in German has always been bad. This is going to be long, but keep reading. If you want to understand why your career is such a mess and what the threat is facing our discipline right now, you have to stop believing that the way things are now is simply how things have always been.

When we say that the job market is good or bad, what we are really referring to is the ratio of available tenure-track (TT) academic jobs to the number of applicants with Ph.D.s. We could push on this definition in some places, but overall it’s fairly robust. A wealth of part-time or temporary non-tenure-track (NTT) jobs does not make for a good job market, and the Ph.D. has been a minimal qualification for tenure or tenure-track employment at most colleges and universities for the time scale we’re concerned with here.

We also need to talk about our data sources for the number of jobs and the number of doctorates granted. We can’t rely on MLA reports about the job market because we don’t have degrees in “MLA,” we have degrees in German. Our field has not developed in the same ways as English or French or Spanish. We need to look at German-specific data for a longer time frame than most MLA reports provide if we want to understand our discipline.

For German, useful data sources include the ADFL/MLA Job Information List (JIL) and the annual “Personalia” listing in Monatshefte. (The Survey of Earned Doctorates would be more accurate and likely find somewhat higher numbers of Ph.D.s, but it does not at present allow for discipline-specific queries in the humanities.) The farther back you look, however, the less easily accessible the data become—and this was as true fifty years ago as it is today. The sad fact is that when your advisor’s advisor, or your advisor’s advisor’s advisor, made some poor decisions that harmed German Studies for a decade or more, no one was paying attention.

I. How the MLA Job Information List created the crisis in the humanities

As a data source, “Personalia” is imperfect. It relies on annual surveys sent to department heads, and the response rate is less than 100%. If you have never filled out one of the surveys, the first time is bewildering, and the next time isn’t much better. The surveys are sent out early in the year and due in June, when departmental staffing is often still in flux. Do you count the guy who taught for you this year but is leaving, or the guy you hired but who hasn’t set foot on campus yet? Flip a coin. Eventually people’s names appear there, tenure-track hires more quickly and regularly than NTT hires, but there can be a delay before names appear, and new appointments can show up two years in a row. Completed dissertations are no better. As the “Personalia” editor complained in 2000, the number of reported dissertations was 20% higher than the number of reported dissertation titles. At least “Personalia” is now keeping count. Before 1980, there were no summary tables, so if you wanted to know how many people were earning doctorates in German, you had to count dissertations by hand. Before 1980, there were also no summary tables of new appointments (which “Personalia” has never broken down between TT and senior tenured appointments). Before 1973, there wasn’t even a list of new appointments; you have to go through all the departmental listings and find the people marked as new appointments on your own. Despite its limitations, “Personalia” reveals quite a bit about what happened to German, as long as you know what to look at. Somebody should have been watching at the time. Today, we’re 50 years too late.

Our other data source is found in the MLA job lists. The MLA did not begin publishing a job list until November 1966. It’s initial effort, Vacancies in College and University Departments of Foreign Languages for Fall 1967—we’ll call it the FVL, for “Faculty Vacancy List”—was actually quite good. Owing to popular demand from departments seeking to find candidates, the MLA began publishing lists of job ads with standardized formatting three times each year. Here’s a typical ad for a job at San Diego State College (today’s SDSU) for fall 1967:

Even without referring to the key provided in the FVL, it’s clear what this job expects and offers. The German jobs were interspersed with all the other languages, and they appeared in order by state, but the “G” in the margin makes it relatively easy to find the jobs you would qualify for. (If you’re curious—or envious—the salary range given in 1966 translates to $59,500-$68,800 in 2013 dollars.) The FVL maintained this form through 1970 (you can access the complete archive from the MLA website).

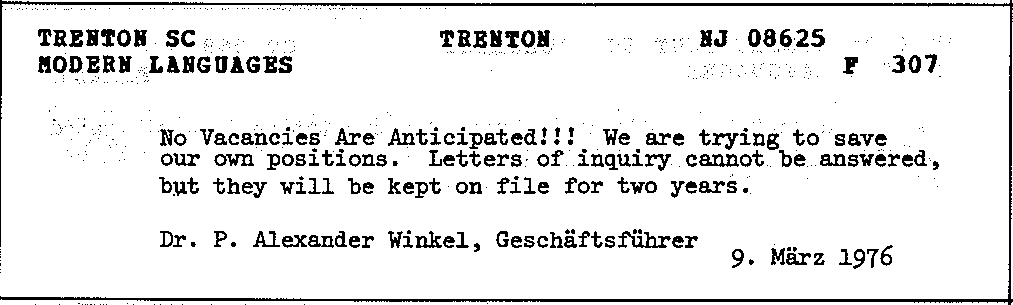

Beginning in 1971, however, things started changing. The March 1971 issue of the FVL dropped the language codes from the margin, making it difficult to find jobs in your field. The entries were not as uniformly formatted. For the first time, the FVL included at the back a list of departments with no vacancies, which was intended to let job-seekers know where they should not waste their time on fruitless inquiries.

Then in the fall, the first issue of the JIL appeared, which replaced the FVL’s accessible and uniformly formatted list of actual openings with a hundred pages of fear and loathing. Instead of listing jobs openings, the JIL aimed to print brief reports on hiring needs from every department in the U.S. and Canada, arranged not by language or by state but by ZIP code. Imagine going on the market in fall 1971, and opening up the new JIL that had just arrived in expectation of finding a list of jobs you could apply to, and finding this instead:

It goes on like this for over a hundred pages. Who was this supposed to help? If you look through all the ads, there are actual jobs being advertised, but they’re not easy to find. (My theory is that the new JIL turned a momentary if serious downturn into a massive collective freak-out that has hovered over the field for four decades.) In December 1976, the JIL went back to ordering the ads by state rather than by ZIP code, as the FVL had done, but it didn’t start arranging job ads by language until 1997. In 1974, it moved the “no information received by press deadline” announcements to a separate section in the back of the JIL, and the “no vacancy” notices followed them the next year, as the FVL had done in 1971. But by then the damage was done. For keeping track of what was going on at the time, or for reconstructing it today, the transition away from the old FVL to the new JIL in 1970-71 came at the worst possible moment. The sheer toil of finding relevant job ads (and then collating them between lists to avoid duplicates) makes it extremely difficult to track the number of openings from year to year. But eventually, the bad things that had been done to German Studies couldn’t be ignored any longer.

II. The Sixties revisited: How your advisor’s advisor ruined German Studies (for a while)

Your advisor did not make a mess of German Studies. The people who did—your advisor’s advisor, or advisor’s advisor’s advisor and his friends—have been dead or retired for decades. Here’s what went wrong: If we take 1960-61 as our baseline (with 32 Ph.D.s in German, it was identical to the average for the late 1950s), then the number of Ph.D.s earned each year tripled by 1966-67, and doubled again by 1972-73 to reach an all-time high of 204 (see Figure 2, and remember that “Personalia” probably understates the number of doctorates). Some of the expansion was justified; thanks to the GI Bill and the Baby Boom (not to mention Vietnam-era draft deferments), undergrad enrollments were booming, new colleges and branch campuses were being founded, and new departments were being formed. Between fall 1959 and fall 1969, total enrollments jumped from 3.6 million to over 8 million. But a jump of 120% in enrollments didn’t in itself call for an increase of over 500% in the number of Ph.D.s in German.

Figure 1: Doctorates granted in German, 1957-1980

Even worse, hiring new faculty in German reached its peak by 1967 and went into sharp decline by 1969, but the number of new Ph.D.s kept rising into 1972.

Figure 2: Ph.D.s versus new TT/tenured appointments in German, 1957-80

The number of doctorates granted didn’t decline substantially until 1976, while between 1977 and 1981 it declined to the same level that persisted over the next few decades and continues up to today.

Figure 3: Doctorates granted in German, 1957-2011

Tripling the number of Ph.D.s to 90-100 per year in the 1960s would have been sufficient to supply faculty needs, so the ramping up of graduate faculty and grad student enrollments should have leveled off in the mid-1960s, but the department heads kept the party going well into the 1970s. They never had to pay a price for the strategic error they made in 1964-66. Their Festschriften, published back when presses still published Festschriften, have long since been moved to remote storage.

If we look at the number of TT job ads in the FVL/JIL and the number of new appointments in “Personalia,” it’s clear that 1970 was not a great year for job-seekers in German. (There is a one-year offset between the two sources, which otherwise track each other fairly closely. For the sake of synchronicity, all the numbers reported here use the hiring calendar of the academic year as their base, so “1970” includes job ads placed between October 1970 and July 1971, for which new faculty started employment in fall 1971 and appear in the fall or winter 1971 issue of “Personalia.”) In terms of long-term trends, however, 1970-71 was a short blip followed by a quick recovery to the level that would prevail for the next 30 years. The go-go days of 1967 were gone, and there were up and down years (1982 was another stinker), but over the long term, the market was relatively stable.

In order to provide meaningful figures, I’ve applied a standard definition of “TT job ad” for all years from 1957 to the present that includes only TT jobs published in the official MLA JIL. Senior-level, part-time, one-semester, and visiting positions are excluded, as are jobs open to any language or requiring multiple languages. This required making judgment calls in some cases when an ad was unclear about rank or the necessity of a second language, but I’ve tried to be fair. I counted all ads for instructor-rank positions as NTT, although promotions from instructor to assistant professor were not uncommon in the 1960s. If you disagree with my counts, I invite you to apply your own definition and judgment to 48 years’ worth of job lists.

There are a few more caveats about the earliest numbers. Departments were more likely than they are today to place an ad and collect applications before administrative or budgetary approval for a new hire was in place, so the appearance of an ad did not guarantee the hiring of a new faculty member (as is also the case today, however, as anyone knows who has ever sent in an application to a canceled search). The FVL/JIL also did not cover the market as thoroughly as it does today; there was a separate “Cooperative College Registry” for many liberal arts colleges, and some departments didn’t trouble themselves with anything as pedestrian as want ads at all. As J Milton Cowan, director of the Division of Modern Languages at Cornell University, stated in the first issue of the JIL:

With that in mind, here is the development of job ads and new appointments between 1966 and 1973 (the MLA archive is missing the JIL issues for November 1969, May 1972, October 1972, February 1973, April 1973, and May 1975, so I’ve tried to use reasonable estimates based on averages from prior and following years).

Figure 4: JIL/FVL TT ads and “Personalia” new apointments, 1966-73

These are steep declines in a short time, but the decline in TT/tenured placements, at 50%, is significantly less than the 65% decline in job ads; the transition from the FVL to the JIL appears to have exaggerated the market decline somewhat. The largest decline is in the new NTT appointments. Between 1963 and 1971, they declined by 85%—but this reflects both a slowdown in hiring, and a redefinition of entry-level positions away from instructors, who were often hired ABD and promoted upon completing their dissertation, to assistant professors with Ph.D. in hand.

If we extend our coverage with JIL TT ads and “Personalia” tenured/tenure-track placements from 1960 to 2007, the number of jobs available remains largely stable. I’ve added a three-year moving-average trend line to smooth out some of the annual volatility. Once we get into the late 1970s, the number of job ads and placements floats around between 40 and 70. The early 70s end up looking like a period of recovery following the steep downturn of 1969-71.

Figure 5: JIL TT ads and “Personalia” new TT/tenured appointments, 1960-2007

In other words, we should stop talking about the difficult job market of the 70s, 80s, or 90s, as this overlooks the 30-year stability in the market between the late 70s and 2007 and the particular circumstances of the 1970s. The rapid build-up of the American university system in the 1960s created a brief burst of intense hiring that had peaked by 1967 and declined to a more sustainable level by the end of the decade. The job market wasn’t ever easy; it required work and talent and connections and luck, but over a long time scale, the job situation in German from the late 1970s until 2007 looks relatively stable. It’s true that the early 1970s were laboring under the consequences of a severe overproduction of Ph.D.s, but job seekers in 1972 also benefitted from the second-highest number of TT job ads in recorded history.

III. 2008: The Bottom Falls Out

Things changed in 2008. This is the part that some people refuse to accept: The job market today is not like the job market of 1977-2007. It is quantifiably much worse.

We have JIL data for 48 years. The last six years, from 2008 to the present, are six of the worst eight years ever, including the four very worst. While it’s true that 1970 and 1982 weren’t great, they were one-year downturns followed by recoveries. For as long as the national job market in German has existed, it has never seen a period of sustained decline in tenure-track jobs like we have seen since 2008, and it has never fallen this low. The last time there were fewer TT or tenured placements than the 16 and 21 of 2009 and 2010 (and 2012 and 2013 will be similarly low) is unknown. It lies farther back than 1957. No year from 1957 to 2008 was worse.

Figure 6: JIL TT ads and “Personalia” new TT/tenured appointments, 1966-2013

Keep in mind that the more important line for job seekers is the green one, the number of ads for TT jobs that they can apply to. The blue line for TT/tenured placements in “Personalia” includes all kinds of hires, including spousal hires and senior appointments. For the thirty years between 1978 and 2007, the average number of TT job ads is 58; for the six years since 2008, the average number is 30.

At the outset I mentioned that the measure of the job market is the ratio of Ph.D.s to available TT jobs. We can graph that ratio over time using data from “Personalia” and the JIL. To estimate the ratio, it’s necessary to look at the number of new Ph.D.s over multiple years, as candidates are not only competing against Ph.D.s from their same cohort. As 95% of people are in their last year ABD or in the first three years after completion when they are hired into their first TT job (this number is not guesswork, but instead based on dates of degree completion and first hire for TT hires since 2006), each dot below represents the ratio of Ph.D.s over four years (in the given year plus two previous years and one following year) to the number of TT job ads that year. The solid three-year moving average trend line smoothes things out over three years to better characterize the period that an applicant might spend on the market. For job seekers, the market improves when there are few Ph.D.s and more positions, and declines when there are fewer jobs and more candidates.

Figure 7: Ratio of Ph.D.s to TT job ads (four-year moving window with three-year moving average trend line), 1966-2013

As you can see, between 1966 and 1970, the situation goes from brilliant to horrible very quickly before settling down to medium bad. If we look at how the ratio changes, we would say that the best time to look for a job in living memory was the 80s, while the 90s through 2007 were almost as good, and the 70s were notably worse, due to the nigh number of Ph.D.s. The period from 2008 to the present is much worse than the 70s. (The graph assumes that Ph.D. production in 2012 and 2013 was no higher than the average for 2000-2011, although the number in 2011 was significantly above average at 104 doctorates granted.) It’s true that 1970 was a bad year, but we’re currently looking at a bad decade with little prospect for improvement. The December 1972 JIL claimed that 87.5% of foreign language Ph.D. recipients the previous year had found full-time academic teaching positions; the December 1973 JIL claimed a placement rate of 72.5% specifically in Germanic languages. No one would claim we’re close to matching that number today.

There’s another important difference. The problem in the early 70s was one of Ph.D. oversupply. Compared to later figures, jobs were plentiful; there were simply too many job-seekers. What changed in 2008 was not the number of doctorates, however, but the number of TT jobs. Ph.D. production has been essentially unchanged since the late 70s (an average of 78 per year in the 80s, and an average of 75 per year in the 2000s). Nor is it the case that Ph.D. production is outstripping the growth of undergraduate enrollments; undergrad enrollments rose over 40% between 1999 and 2010. So where’s my academic job boom? The roots of the problem of 1970 and the problem now are entirely different. The 70s addressed the problem of oversupply by cutting back on production. Who’s going to address the problem of underprovision of jobs by increasing TT openings?

It’s not that there are no jobs out there. There are contingent and part-time adjunct teaching jobs. When it comes to hiring contingent faculty and adjuncts, the profession is still partying like it’s 1969.